Paris, an Empty Library, and a Photographer’s Obsession

From Love to Loneliness: Masahisa Fukase's Ravens

August in Paris is the best-kept secret. The air is softer, the streets are slower, and with most Parisians gone, the city finally exhales. On a quiet Wednesday afternoon, my plans to meet a friend for a photowalk fell through. So I decided to do something I’d been meaning to for ages: get the annual pass to the Maison Européenne de la Photographie—and finally explore their library.

The plan was simple: flip through photobooks and editions long sold out, treasures tucked away. I “borrowed” my boyfriend’s jean jacket (we all know what that means), dabbed on pink blush, and rushed to the museum.

No one was there. The silence felt like a gift—an entire library to myself.

You can’t browse the shelves directly; you have to request a title from the librarian. After a pause, I started with one of the most acclaimed photobooks of the last century, Ravens by Masahisa Fukase.

Probably the most obsessive photographer of the 20th century

I first encountered Ravens at the Rencontres d’Arles in 2017. I didn’t know Fukase then, but I walked out of that exhibition changed—especially in how I saw “intimate photography,” a genre deeply rooted in Japan, where art and personal life often blur.

I don’t want to make this a whole essay about Fukase’s life and work, because I’m not an expert, but in short: Fukase grew up in Hokkaido, in a family which owned a local photo studio. Instead of taking over the business, he moved to Tokyo, worked in commercial photography, and eventually dedicated himself entirely to personal projects—photographing his cat, his wives, his family, himself.

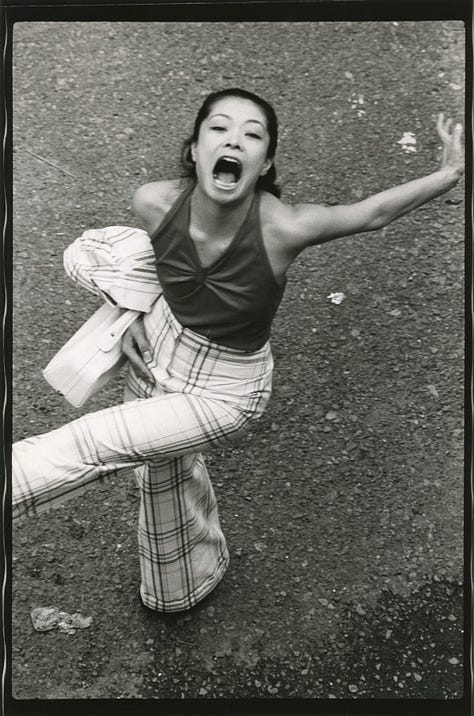

What struck me was his obsession. He captured his life relentlessly, compulsively. His series From Window shows his wife leaving for work each morning, framed in the same window—even as their marriage was crumbling.

When I think about it, I was born into photography and my life has always revolved around photography. There’s nothing I can do now, but I always forced the people I loved to become involved for the sake of my taking photographs, and I couldn’t make anyone happy, including myself.

Masahisa Fukase

When she left, he spiraled into depression. Traveling back toward his hometown, he began photographing ravens. For years, he pursued them until, in his words, he had “become a raven” himself. This marks the creation of his masterpiece.

Loneliness in black wings

The book is a storm of images—dark figures in flight, caught alone or in flocks, often at dusk. Flash catches their eyes like tiny mirrors in the shadows. Each frame feels electric, charged with loneliness.

This is Fukase’s genius: he doesn’t show loneliness through the obvious. He transforms a symbol into something personal yet universally understood. As David Travis wrote for the book’s introduction:

Of those who made photographs of experience lived and felt, only a very few could sustain the intensity of that experience and make it into something larger than an immediate visceral scream.

David Travis

It’s a lesson that sticks with me: how do you move beyond what’s visible, to photograph something that feels rather than shows?

The outside for the inside

One sequence in Ravens still haunts me: a frozen raven, a cat, and a naked woman (a masseuse, probably encountered by chance?). The simplicity of the frames makes the emotion hit harder.

The sadness in the image hints at the complex emotions the lonely, middle-aged man must have felt behind the lens.

Fukase spent his life trying to stop time through photographs. In a twist of fate, he fell in 1992, slipped into a coma, and remained there for 20 years until his death in 2012.

As I closed the book in that empty library, I thought about his words:

I never think that I can capture a certain subject by taking a photograph of it. What is important for me is how deeply I can enter into it, and to what degree I can cause it to reflect me.

Masahisa Fukase

Maybe that’s the real challenge—not to capture what we see, but to let the outside world mirror the inside, until the photograph feels inseparable from the photographer.

Normally, I took the annual pass at the MEP to save money—why buy pricey photobooks when I could flip through them in the library? But that afternoon, as I walked into the metro clutching a fresh copy of Ravens I’d just picked up at the bookstore nearby the library, I had to laugh at myself. Classic case of “girl math”: convincing myself that buying the book was actually some kind of smart investment.

Who was I kidding? When it came to photography obsessions, resistance was pointless.

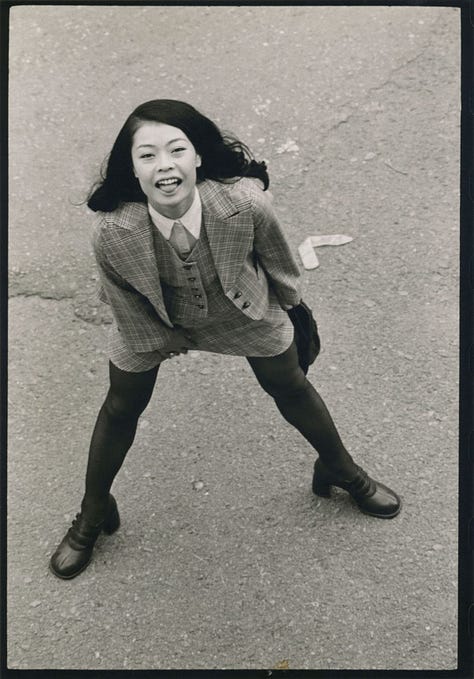

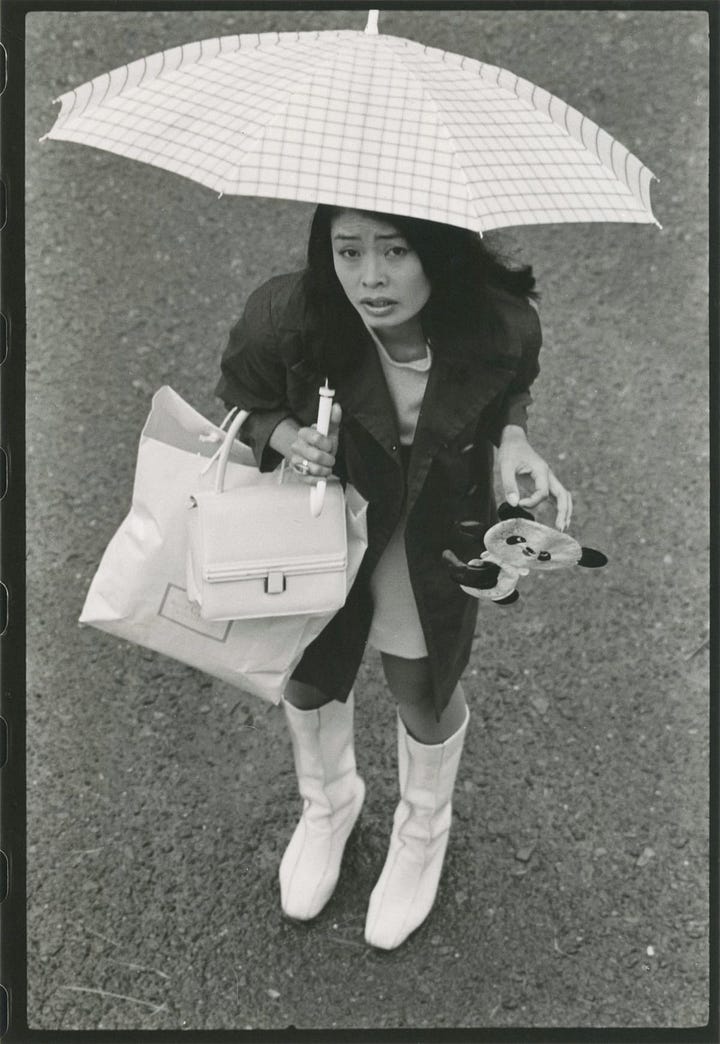

The photos I liked this week on Instagram:

Thank to you Léa, I have discovered that the MEP has a library !!!!

wow!!! these photos remind me to find art in simplicity. makes the emotions really show